Father of candid photojournalism. Alfred Eisenstaedt, a man who carried his humble 35-mm Leica camera everywhere he would go, is now being commemorated at the San Diego Museum of Art’s new exhibition, “Alfred Eisenstaedt: Life and Legacy.” The Balboa Park museum is exhibiting a photographic assortment of over 350 of Eisenstaedt’s most significant photographs mostly from his work at LIFE Magazine. The exhibit focuses on the life and history of Alfred Eisenstaedt and celebrates his accomplishments through his photographs.

Eisenstaedt was born Jewish in Dirschau, West Prussia, Imperial Germany (modern-day Poland) in 1898. In 1906, his family moved out to Berlin where Eisenstaedt decided to dedicate the majority of his life to photojournalism. He studied at Humboldt University of Berlin and served in the German army during World War I. Injured by the war in 1918, he employed himself as a belt and button salesman in Weimar, Germany. By 1928, Eisenstaedt was working as a freelance photographer for the Pacific and Atlantic Picture Agency’s Berlin office, which was then taken over by the Associated Press in 1931. Within a year, he was described by the people as a “photographer extraordinaire,” which led him to be hired by Ullstein Verlag, the largest publishing house in the world at the time. It was then where he was qualified enough to photograph the notable first meeting between Adolf Hitler and Benito Mussolini in Italy. A staggering image, taken years before the second world war and also years before their names became a synonym for evil.

His portrait photographs are definitely the most compelling. Eisenstaedt held expertise in capturing unique expressions off of his subjects. His angles are favoring to his subjects, he does justice to photographs of Katherine Hepburn and Betty Davis, both from 1938.

Two years before World War II, Eisenstaedt was forced to flee Nazi-Germany to the United States where he freelanced for Harper’s Bazaar, Vogue, Town and Country, and other top-notch publications. In 1936, Henry Luce, who was called “the most influential private citizen in the America of his day” by American historian, Edwin Herzstein, hired Eisenstaedt and helped debut LIFE Magazine. Eisenstaedt shot photographs for LIFE from the day they debuted until they stopped publishing as a weekly in 1972. After LIFE was shuttered, Eisenstaedt proceeded to take his photographs and received the ICP’s Infinity Master of Photography Award in 1988. His career with photographed ended when he passed, in 1995.

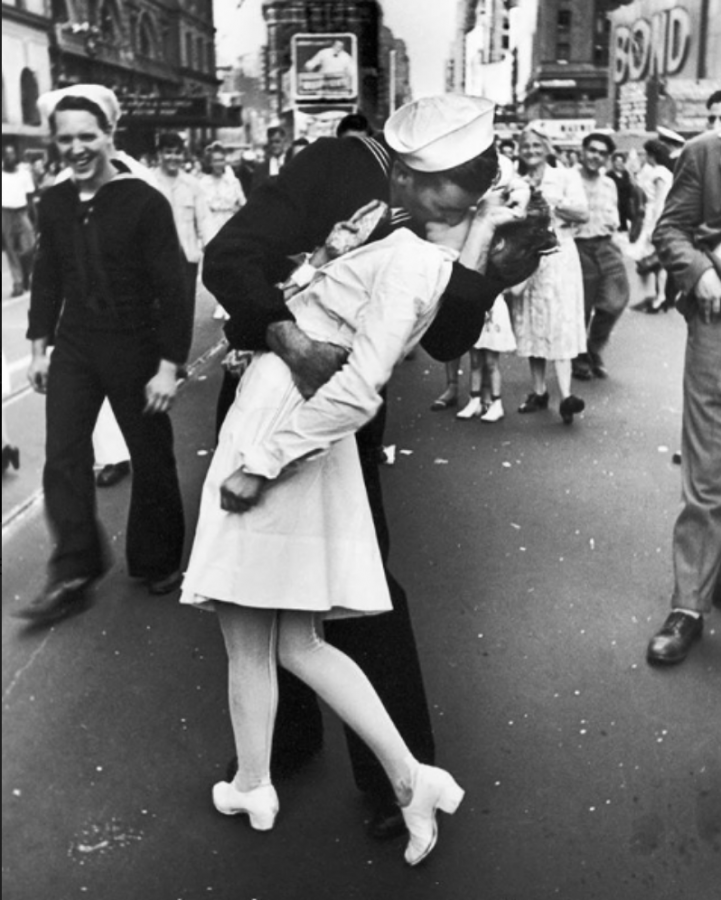

Eisenstaedt is responsible for the most memorable photographs of the 20th century, including, V-J Day in Times Square, which portrays a U.S. Navy sailor grabbing and kissing a female stranger in a white dress, a photograph most San Diegans are familiar with, in reference to the 25-foot statue by Seward Johnson.

Now, the San Diego Museum of Art in Balboa Park is offering a unique exhibition of Eisenstaedt’s work. The collection offers his unique gelatin silver prints of the naturalistic and intimate facial expresses made from a variety of his social subjects from the 1930s to the 1950s. The span between these decades is now regarded today as, “The Golden Age of Photojournalism.” There was a time where glowing-TV screens and the internet weren’t commonplace, so it was these Eisenstaedt’s photographs that were instrumental in transporting people from their homes to experience distinct people, places and culture, something they would otherwise not be able to visualize. The exhibition is on view until July 14.