Prize-winning journalist Jose Antonio Vargas shared his views on immigration, his life as a gay Filipino man, and his journey in America as an undocumented person, in his “Defining American” webinar.

This webinar was made possible by the Justice, Equity, Diversity and Inclusion (JEDI) Council, a collaborative of community colleges within the San Diego region, to commemorate Filipino American History Month, LGBTQ+ History Month and Undocumented Student Week of Action.

At just 12 years old, Vargas made the journey to America, to live with his grandparents and seek out a better life. In 1997 at the age of 16, he never knew that an exciting trip to the DMV to obtain his permit would turn into a life-changing moment. He was told by the DMV employee that his Green Card was fake, meaning he was in America without authorization from the government. This event would serve as the catalyst for the work that he continues to do today.

Salvation for Vargas came in two forms. First, he recalls his teacher telling him that “he asked too many annoying questions and should consider being a journalist.” “I thought if you became a journalist you get to write, and then your name would be on a piece of paper,” he said. “And that’s literally why I became a journalist. To see my name, my real name on a piece of paper. In a way I wanted to write my way into America.”

His admiration for the best-selling author Toni Morrison also served as another form of salvation for Vargas, specifically her best-selling book titled “The Bluest Eye.” In a PBS interview with Morrison and American journalist Bill Moyers, Morrison discussed the meaning of the phrase “the master narrative,” a concept she focused on in her book. Morrison said, “the master narrative is whatever ideological script is being imposed by the people in authority on everybody else.” In response, Moyers refers to the main character in the book as the “perfect victim” for giving in so easily to that ideal. This impacted Vargas because he decided he didn’t want to be the perfect victim to the idea that human beings could be considered “illegal.”

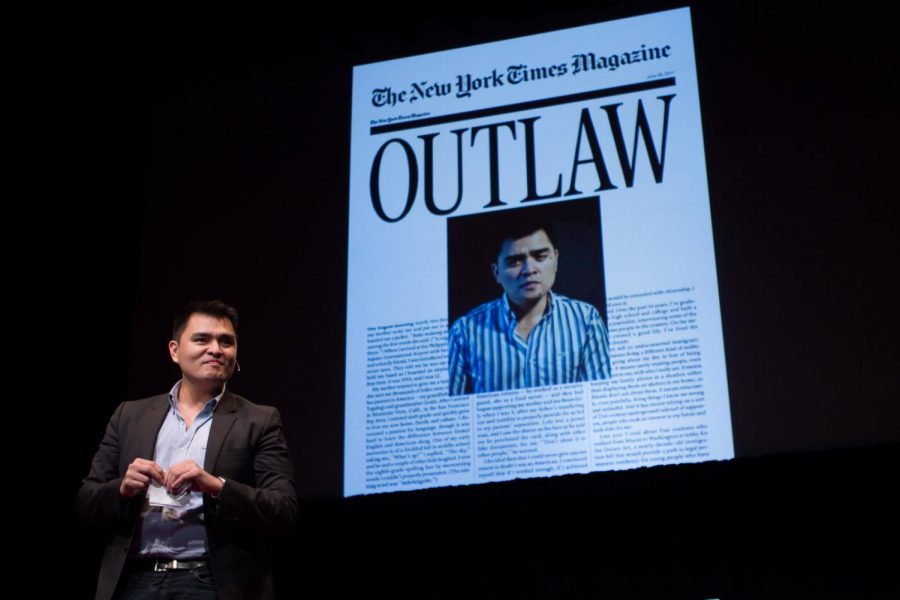

In a bold move, Vargas chose to disclose his undocumented status to the world in June 2011. He wrote a lengthy article that was featured in The New York Times Magazine, detailing his life from the moment his mother put him in the cab to the airport in the Philippines, to his life up until that point. When asked by many why he would ever expose himself as being an undocumented person he said, “In a society where my existence is defined and limited by laws that haven’t even passed, freedom for me came from owning and telling my own story.” He touched on and challenged the listeners to consider the hypocrisy of the anti-immigrant narrative that this country faces. “We identify undocumented farmers whose labor we cannot live without as essential workers, yet not essential people,” he said. “Certainly not essential enough to qualify for economic relief during the pandemic, right?”

In another bold move, Vargas called the Immigration and Customs Enforcement agency to question them as to why they hadn’t come to deport him yet. Once the ICE agent told him “They can’t comment on his case,” he realized what was really going on. “So long as you get the labor, so long as you get what you need. You don’t really want to pass the law, it’s not a priority,” he said. “We live in a country where legalizing marijuana is more mainstream than legalizing people.”

“To be undocumented, gay, and Filipino…means to me, not surrendering to the master narrative of what people think that undocumented, gay, and Filipino means,” Vargas said. “I am actually not a minority, I am only a minority under laws in which being, gay, undocumented and Filipino are codefined as inferior and treated as other.”

And with this realization, Vargas along with the help of colleague Jake Brewer, founded the “Define American” organization in 2011. “Define American is a culture change organization that uses the power of narrative to humanize conversations about immigrants. Our advocacy within news, entertainment, and digital media is creating an America where everyone belongs.”

When asked how he would define being American, Vargas had this to say. “I think people who have to fight, people who actually have to struggle to be American are the most American people. If you actually look at the history of this country, that’s the majority of people…I would argue that in this country, being American is something we have to fight for. And I think in some ways that fight, the resilience that it takes, makes someone American.”