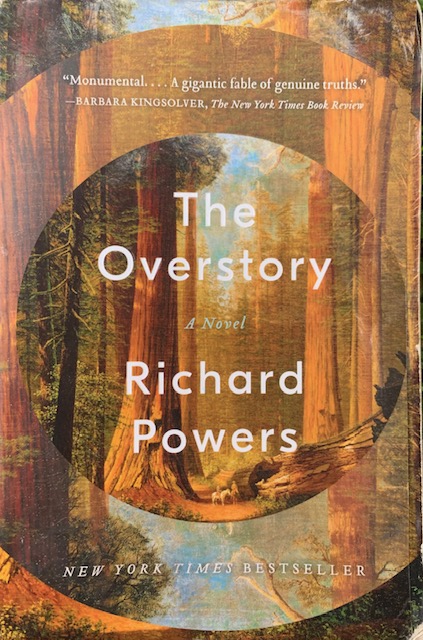

As San Diego becomes sunny once again, Balboa Park fills with local residents, tourists, and furry friends. They explore trails, visit museums, and walk through resplendent flower bushes eager to greet spring. According to Forever Balboa Park, there are approximately 16,000 trees in the park and San Diego Reader reports over 400 species. After reading “The Overstory” by Richard Powers, you’ll never walk through Balboa Park the same.

“The Overstory” is a brilliant eco fiction that sheds light on the extraordinary life of trees and humans’ relationship with them. It explores this relationship using nine characters with vastly different life experiences. In leading with nine main characters as opposed to one, Powers brilliantly criticizes the human tendency to believe themselves to be the pinnacle of existence. In doing so, he creates a space for a surprising tenth main character: trees.

Instead of chapters, “The Overstory” is divided into four sections: Roots, Trunk, Crown, and Seeds. Each section is eponymous of a stage in each character’s development. Like Dr. Patricia Westford says on page 454 of the book, “Men and trees are closer cousins than you think.”

Like all good things, the book unravels slowly. The book’s impact is largely due to the amount of time Powers spends setting the scene for each character in Roots. However, the book’s most impactful contribution is its scientific language. Indigenous peoples of this continent have believed that trees have spirits for hundreds of years. Nevertheless, ideas such as these have been dismissed at best, and ridiculed at worst, for their lack of academic validity. Powers’ integration of modern research allows these ideas to be explored with an open mind by those that would usually dismiss them.

According to Suzanne Simmard, a Canadian ecologist who now teaches forestry at the University of British Columbia, trees communicate with one another. She found that forests, which have been traditionally viewed as competitive, are actually cooperative, and that this communication and cooperation amongst trees are one of the reasons behind forests’ resilience. Simmard is one of many trailblazing scientists anthropomorphizing and redefining trees as the sentient beings indigenous peoples have long known they are.

Dr. Patricia Westford, one of the main characters in the novel, is an ecologist who’s voice throughout the book echoes that of Suzanne Simmard in the real world. Adam Appich, another main character in the novel, is highly regarded in the academic realm of psychology, and he is introduced in Trunk as a psychology graduate student at UC Santa Cruz working on his thesis. Adam’s voice in the novel also leads with major psychological principles, primarily in the realm of social psychology, which allows the reader to take the real science alongside each character’s story, and digest the novel accordingly.

The book is a Rosetta Stone for anyone seeking to connect deeper with themselves and the wisdom nature has to offer. We may not live in the middle of a forest, but plants -– trees, are more ubiquitous than we may realize. At a time when climate activism is of utmost importance, deep immersion in the natural beauty all around us is vital.

“What’s crazier — plants speaking, or humans listening?” one character asked another on page 322 of the novel. It’s a million dollar question, and one you may have a different answer for after reading “The Overstory.”