According to the President of the American Federation of Teachers Guild Local 1931 Jim Mahler, adjunct professors in the San Diego Community College District make less than half the salary of their full-time counterparts, despite performing the exact same tasks and being required to posses equivalent qualifications. In turn, he says, students are being deprived of the education they deserve due to the inaccessibility of their professors and lack of resources.

In order to alleviate this issue, Mahler sent Governor Jerry Brown a letter on Oct. 23, 2014 requesting that specific provisions be included in the January 2015 budget to shrink the disparity that exists between full-time and part-time teachers’ salaries. The effect would be two-fold: offer dignity, equity, and fairness for temporary, part-time community college faculty and enhance student success.

Specifically, the resolution calls for $50 million in new resources to increase the salaries of temporary, part-time faculty as a first step toward achieving pay equity with their tenured/tenure-track colleagues, $30 million in new resources to fund their office hours, and $100 million in new resources for the conversion of existing part-time temporary faculty to full-time faculty status.

According to adjunct Geoffrey Johnson, this is a necessary step that “California can afford.”

The San Diego Community Colleges District participated in Campus Equity Week this year during the week of Oct. 27-31, which featured numerous events and talks purposed to boost awareness of the adjunct crisis, serve as a platform for further action and inspire students and teachers to get involved.

“The pay inequity between part-time and full-time faculty is an affront to justice, and the failure to speak out is hypocrisy and complacency,” says adjunct professor John Hoskins. He explains that the inequity that part-time professors are forced to live with is simply unjust and demoralizing.

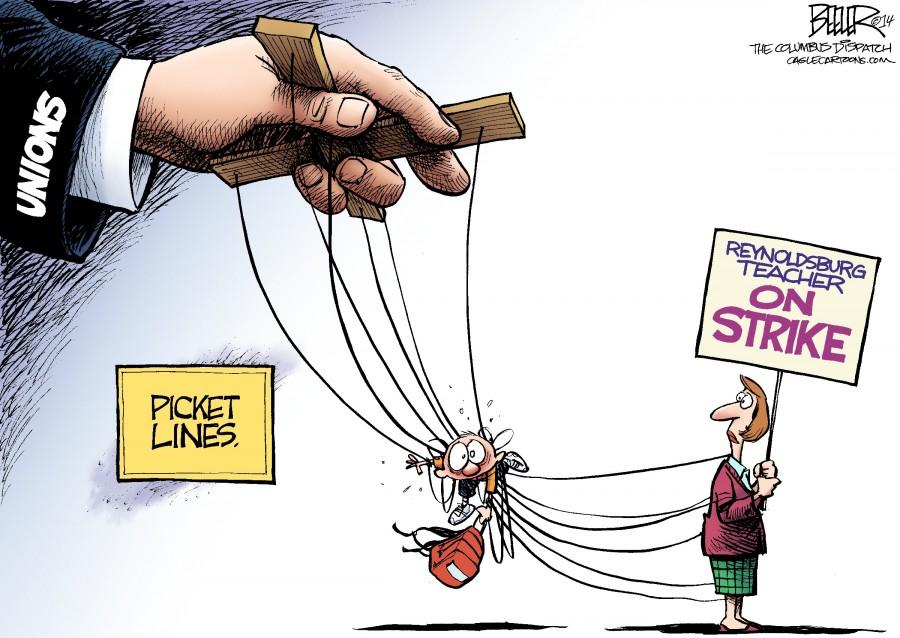

“…we live less-than lives, with less-than careers, and never pay back our student loans,” he says. “The point I want to make is that we tend to rationalize the best scenario… rather than demand justice…because we feel powerless.”

Furthermore, Mahler encourages people to participate in this movement by sending letters to the Governor and other California politicians.

President of San Diego Mesa College Dr. Pamela Luster agrees saying, “I am supportive of this statewide effort to encourage the Governor’s office to consider increased funding to bring higher wages to our adjunct faculty. As someone who started my career teaching part time at 3 different colleges for several years, I understand the inequities that exist.”

Similarly, the Dean of the School of Social/Behavioral Sciences and Multicultural Studies Charles Zappia believes that public employees deserve equal compensation for the full value that their labor produces.

“Educators, from pre-school through graduate school, deliver one of the most critical services necessary to the health and welfare of a society,” he says.

In his support for uniform pay for adjuncts, he includes that salaries are bargained collectively within the system, and deans have no influence in setting those numbers.

Zappia’s recommendation, which speaks only of his own opinions and not for San Diego Mesa College Administration as a whole, is to “greatly increase the number of tenure-track positions in higher education generally,” while preventing any “further erosion of the valuable tradition of tenure”.

Not only do part-time professors make significantly less than full-timers (approximately $53,934 less), they also rarely receive health coverage and/ or compensation for office hour time outside of class to meet with students.

The reality is that most adjunct professors are, in fact, teaching full loads, with their classes spread across two or three locations and a large portion of their days spent driving to and from campuses. The largest problem stemming from this disproportion is that students are not receiving the attention that they deserve or given the best opportunity for success.

“…it has hurt students, who are often deprived the necessary access to teachers, or the building of a true student-teacher relationship, in that their adjunct teachers are unavailable,” says Johnson.

Mahler, too, explains that when colleges rely heavily on temporary, part-time faculty, they weaken the faculty involvement in student learning and consequently decrease the rates of retention, graduation and transfers. Statistically, for every 10 percent increase in the percent of tenured faculty at a two-year college, the chance that a student will transfer to a four-year college increases by 4 percent.

“In short, the proliferation of adjuncts, and their being underpaid has contributed to lower student completion rates, and in a way, a kind of fraud in that the education that can and should be delivered, is in fact, not being delivered,” concludes Johnson.