In an age of Netflix crime documentaries, murder mockumentaries, and feature-film adaptations about serial killers, exposure for high-profile true crimes has never been more accessible — nor, apparently, has it ever been as sexy.

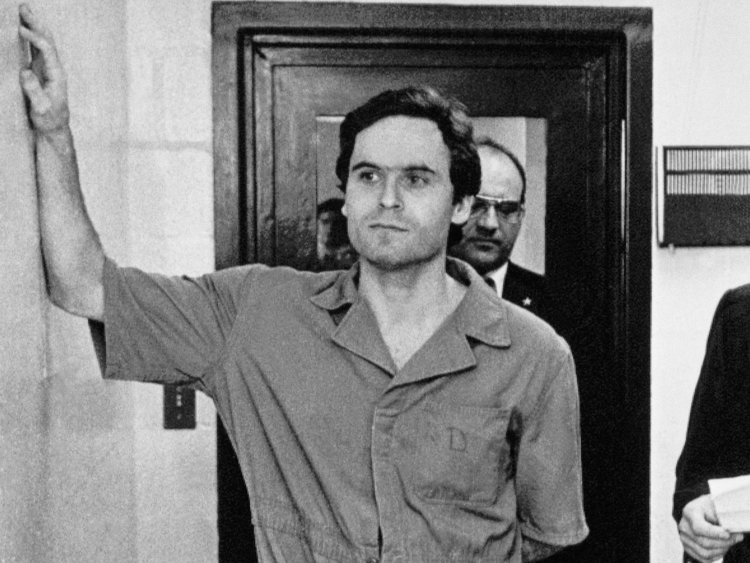

A quick glance through Twitter shows that people on the internet think Ted Bundy was charismatic and attractive, obsessing to the point that Netflix’s official US Twitter account issued a formal statement.

“I’ve seen a lot of talk about Ted Bundy’s alleged hotness,” the tweet said, “and would like to gently remind everyone that there are literally THOUSANDS of hot men on the service — almost all of whom are not convicted serial murderers.”

The use of “almost” is an interesting clarification, but the message sticks.

Another quick glance through Penn Badgley’s Twitter reveals that fans of his new Netflix show, “You,” have fallen in love with his character Joe — despite the obsessive stalking and murderous tendencies. When people sexualize Joe and beg to be kidnapped, Badgley often responds to their thirsty confessions with unsubtle disapproval. “No thx,” he tweeted back at one fan.

All the hubbub begs the question: do sensationalized depictions of criminal and abusive behavior create social norms accepting of those behaviors?

“Lolita,” the 1955 novel by Vladimir Nabokov, is a timeless example of direly misunderstood media told from the perspective of an unreliable narrator. In her journal publication “The Art of Persuasion in Nabokov’s Lolita,” Nomi Tamir-Ghez writes that what “enraged or at least disquieted most readers and critics was the fact that they found themselves unwittingly accepting, even sharing, the feelings of Humbert Humbert, the novel’s narrator and protagonist.”

Unreliable narration, as characterized by TVTropes.com, is when a “consistent and sincere testimony (proves) Unreliable if coming from a perspective of personal bias, or conclusions drawn from incomplete observation.” It’s when a character whose perspective drives the narrative justifies their morally divergent choices.

Nabokov writes from the perspective of Humbert, who believed himself a victim despite falling in love with and ultimately impregnating 12 year old Dolly. But instead of grasping that Nabokov intended to show how corrupt Humbert was, readers empathized with him and vilified the girl he raped.

In a January interview with TVGuide.com, “You” showrunner Sera Gamble said that “there were times that I found myself really rooting for the couple.” She added, “I was sort of horrified at myself and then it caused me to really think about the kind of movies I grew up loving, the kind of love songs I grew up singing — the message that we give our boys and our girls is that certain things are romantic, that in actual life are illegal, and stalking, and not romantic. They’re invasive.”

Stories like “You” and “Lolita” are designed to challenge readers, yes. But commercially successful media which turns abusive tendencies into core tenets of romantic stories still exists. These works cement corrupted ideas about relationships and love in the minds of young readers, likely creating the kind of people who fantasize about homicidal stalkers with boundary issues, or people with fan blogs about Ted Bundy and the Columbine shooters.

Dr. Wind Goodfriend’s 2011 piece for Psychology Today, “Relationship Violence in ‘Twilight,’” succinctly captures the red flags between characters Edward and Bella from Stephanie Meyer’s “Twilight” — a highly successful fictional saga infamous for its romantic depiction of a controlling and generally abusive relationship.

“Twilight” comes from a different place than Nabokov’s “Lolita” in that Meyer’s works are the product of irresponsible narration — writing lacking the self-awareness to present its material as anything other than good and true.

It is imperative that the general public’s reading comprehension and media literacy must advance if content creators continue to present abuse through the eyes of unreliable narrators like Humbert and Joe.

Writers, readers, and viewers alike share a responsibility to distinguish between stories written to romanticize certain behavior and stories written to question that behavior.