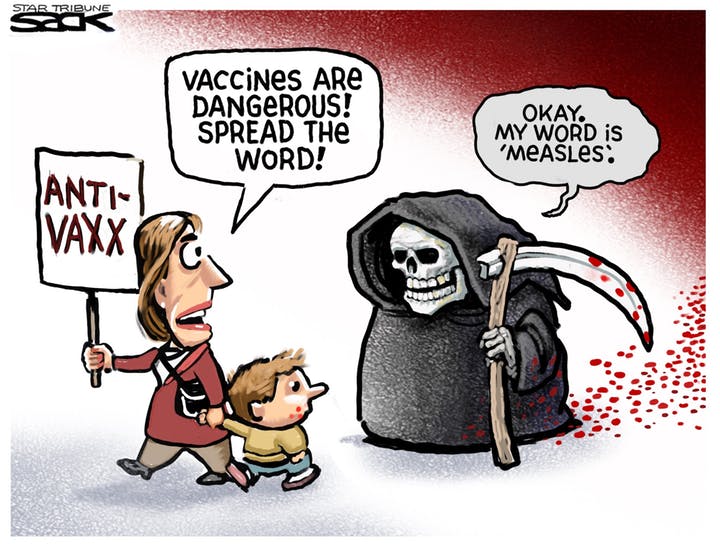

Measles is alive and spreading rapidly in the U.S., thanks to rapid anti-vaccination misinformation campaigns espoused on social media and on the web. Although the disease was officially eradicated in the U.S. in 2000, it has come back with a vengeance, and not just in the U.S.; according to a World Health Organization (WHO) report published recently, “measles cases in the first quarter of this year were up 300% over the same period in 2018.”

Many news organizations covering the measles outbreak in the Ukraine, Oregon and other places have placed the blame of the anti-vaccination campaign solely on the anti-vaxxers themselves; in fact, a CNN article is titled “Anti-vaxxers ‘have blood on their hands,’ says UK health secretary.” But what if it’s not only the anti-vaxxers who have allowed the return of such contagious diseases?

The anti-vaccination movement is not a “both sides” argument. It is not an “opinion” to conclusively assert that there is overwhelming scientific evidence backing up the benefits of vaccines, and little to no scientific evidence backing up the repudiated links between vaccinations and autism. Anti-vaxxers are a threat to public health, plain and simple. But the misinformation they are armed with should be regarded in much the same way in the public eye, since it contributed to the current outbreak.

The anti-vaccination movement did not arise out of anything, suddenly and nowhere. According to a CityLab article from April 24, the Jacobson v. Massachusetts 1905 Supreme Court case established that the state had the right to pass compulsory vaccination laws. The anti-vaccination movement mobilized in response and managed to lobby into effect many of the vaccination exemption laws we see now. In Nov. 2018, an AAP News and Journal Gateway article details how Russian bots have been nearly as busy inciting controversy regarding vaccines as they were sowing discord during the 2016 election. And in rather typical response, Facebook and other tech giants only responded to anti-vaccination campaigns propagated on their respective platforms after facing intense public scrutiny.

So obviously, we can’t just trust the internet to set these people straight, given that “a staggering half of all new parents have been exposed to anti-vaxx material on social media,” according to a Guardian article published April 24. Setting the record straight should fall on the shoulders of news organizations or health departments.

When people think of an anti-vaxxer, what comes to mind is probably a defiant parent who refuses to accept the viability of scientific evidence, despite having handy access to it. And when confronted, anti-vaxxers are sometimes met with ridicule by anyone who trusts the veracity of said scientific evidence. In contrast, a public policy campaign would not ridicule a anti-vaxxer, just present them with facts; public policy campaigns are meant to be objective, after all. Health organizations, who would be undertaking these campaigns, could employ grassroots advocacy within local communities as well to make the point that “big government is not just trying to take civil liberties away,” as many anti-vaxxers believe.

When it is so easy to access conspiracy theories and be caught in an echo chamber of misinformation, it is not enough that the government only fines parents who refuse to vaccinate their children. Governments could do that, but that would probably just help validate the confidence anti-vaxxers have in anti-vaccine claims. And while it is essential that peer reviewed, credible science is used in public policy campaigns, a consistent application of that science in the public sphere is necessary to call out any and all misinformation that is spread. For instance, it would be smart for the current head of the health department to apologize on behalf of Trump and explain why the erroneous claims he made previously regarding vaccines are wrong. It would also be smart to make sure that said public policy campaigns are actually effective, to ensure their continued success in the long run. In addition, news organizations should give coverage to said public policy campaigns and stop giving every interesting anti-vaxxer a microphone.

It’s time to change the way we approach anti-vaxxers. They’re not going away any time soon, but the damage their campaigns cause hopefully can be minimized enough so that measles can at least be eradicated again.