For as long as there have been schools, there has been cheating.

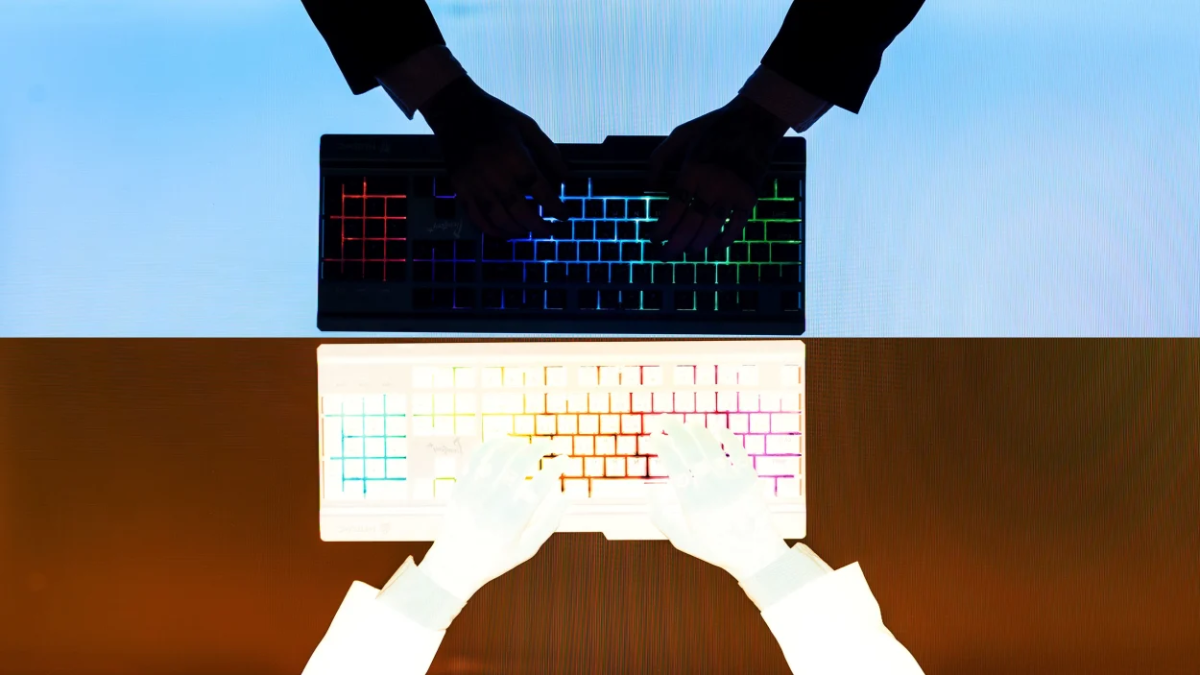

For centuries, students and their instructors have been locked in silent conflict, each trying to outsmart the other’s methods in a war of innovation. In the past few decades, as the world has become reliant on the internet and much of education has moved online, methods of academic dishonesty have rapidly evolved, and teachers have been forced to adapt just as rapidly to the many new ways that students have discovered to cut corners.

To aid educators in their eternal struggle, many programs have cropped up that claim to detect instances of plagiarism in written work. Among the most prominent and widely used of these programs is Turnitin.

Turnitin functions by checking student submissions against its database of books, articles, and other online content. The idea is that, if a portion of a student’s assignment resembles another piece of writing too closely, it will be marked for potential plagiarism. In many ways, this has made teachers’ jobs much easier. Rather than having to painstakingly comb through each individual essay, Turnitin allows teachers to check hundreds of submissions at once, and its algorithm can catch better concealed instances of plagiarism with much greater ease.

Or at least, that’s how the typical sales pitch goes.

The truth is that Turnitin has never been able to detect plagiarism. Rather, it detects similarity. “The two concepts are not the same,” wrote Turnitin Director of Customer Engagement, Patti West-Smith, last October. “You’ll notice we don’t call it the Plagiarism Report or – even worse – the cheating report. We don’t detect those things, and we’re not in the business of making those determinations.” This critical distinction is one that all too many instructors overlook. A student whose assignment is marked with a high similarity score often ends up dealing with a very serious allegation of plagiarism, which there is no good way of disproving.

That’s the other major problem with Turnitin: there is no presumption of innocence. Forcing students to submit papers through Turnitin means they are all assumed to be guilty until proven innocent, and when the program flags a submission as having high similarity to other content, an accusation can automatically become a conviction. The burden of proof is placed upon the student, and they are forced to prove a negative. This is not only unfair, but categorically impossible — especially when the accusation is false. And that is perhaps the most glaring flaw with Turnitin. All too often, it is inaccurate.

As text-generative artificial intelligence programs have exploded in popularity over the past year, Turnitin has rushed to give teachers a way of stemming the tide of essays written by ChatGPT and similar tools. However, as with plagiarism, the use of AI cannot be definitively detected. Instead, AI “detection” is based upon predictions that something was written by an AI program, judging by how similar a student’s writing is to something that an AI would write. Ironically, AI detection programs are themselves powered by an AI, and a faulty one at that. Some students end up getting punished for simply writing in a formal way that bears similarity to how ChatGPT may write.

Turnitin is a powerful and valuable tool. It has allowed educators to cut out much of the menial work that they once had to do when grading papers, and streamlined the process for both students and teachers immensely. However, it is a flawed and imperfect tool, subject to frequent inaccuracies and false positives which create undue stress and waste valuable time on both sides of the gradebook. Although it can be helpful when used diligently, professors shouldn’t blindly follow Turnitin’s assessments of student submissions. Rather than treating it as a definitive arbiter of truth, professors should use it like any other tool, with care and precision.

Trust, but verify.